|

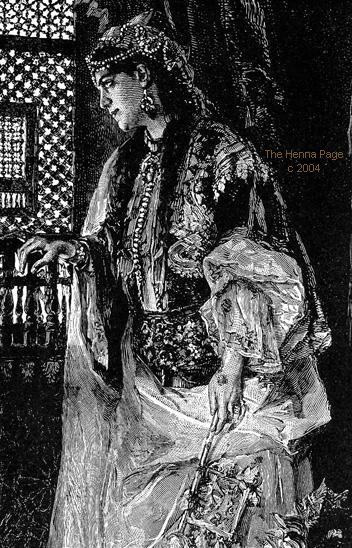

Ottoman Empire Catherine Cartwright-Jones © 2004  Detail from "Circassian Slaves", 19th century lithograph by Allom showing woman with hennaed hands, drawn from high resolution scan by Catherine Cartwright-Jones for The Henna Page, © 2004 Visitors to Turkey during the 19th

century saw brides hennaed for weddings, women using henna in the

hamams, and women

wearing henna for everyday adornment. The illustrations above and below

show typical 19th century Turkish henna patterns: bold areas of henna

and detail within. By the late 20th

century, henna body art had retreated to rural Anatolian villages

with simple dabs and dips, was dismissed as ugly and old-fashioned.

Turkish people were aware of few, if any henna

traditions in Turkey, and other insisted Turks did not "do henna".

From Alev Lytle Croutier's semi-autobiographical book "Harem", she recalls, "At the time of my childhood, henna nights had come to be considered a rural custom and were never practiced in the cities. But I do remember visiting relatives in the c country and, for the first time, having both my hands covered with a gray-green paste that smelled like horse manure and kept getting colder as the evening wore on. My hands next were wrapped up in cloth like twin mummies. I spent a restless night, incapacitated by my wrapped hands, yet so curious of the outcome that I did not dream of taking the bandages off. The next morning, one of the women carefully unwrapped my hands and washed off the hardened mud. Underneath, my fingers were bright orange. When I returned to the city, other children made fun of me. The henna did not come off for weeks, no matter how well I washed my hands, (Croutier, 1989, 149). How had henna art flowered in Turkey after the Turkoman conquest, with its unique Turkoman style patterns for 500 years, then disappeared in 3 generations? The reasons for this retrogression are complex, and are related to the democratic revolutions, social reformations, and independence movements through the 19th and 20th centuries, as the old empires collapsed.  Ottoman woman from late 19th century with henna patterns on both hands: back of right hand, and left wrist. From "The World's Fair"by H. G. Cutler, Chicago, 1892 In the late 19th and

early 20th century, Europe and Turkey increased trade, knowledge, and

political interactions. The Turkish bourgeoisie increasingly

sought European goods, while the European wealthy purchased Turkish

carpets, Orientalist art, and “exotic” Turkish foods and fruits.

The upper classes of each dabbled in the culture of the other.

Wealthy Turkish families hired European tutors for their children,

purchased European fashions, and the acquisition of these European

goods became symbols of affluence and modernity just as Oriental

objects d’art were prestigious purchases for Europeans. Magazines

and motion pictures spread the desire for western standards of

modernity, beauty, cosmetics and fashion. Turkey was increasingly

exposed to the west by the end of the First World War, and vice

versa.

In 1922, the liberal nationalists, the “young Turks” led by Ataturk, revolted against the Ottoman government, in an effort to modernize and westernize Turkey, and overthrow all that they felt was decadent, oppressive, and backwards. The Sultans and the Caliphate were weak and corrupt, and had exploited the lower classes to keep the elites in luxury. Ataturk believed that the only way for Turkey to become a strong, productive modern state was to throw off all archaic beliefs and feudal structures and become egalitarian, rational, and democratic. He legislated that Turkish be written in the Roman alphabet and began language reform. He instituted clothing reform to help destratify social and ethic divisions. He instituted a humanist, secular law and civil code based on Swiss civil code. He gave equal rights and votes to women, and discouraged veiling. Ataturk boldly instituted western reforms against many the symbols of the past that he felt were emblems of ignorance, fanaticism, and hatred of progress and civilization. He promoted ballroom dancing to replace folk music and dance, setting all social occasions into a western cultural model, and to dissolve ethnic and class divisions. He believed that Europeanization was the key to bring his country into the modern era, and did all he could to legislate modernization, westernization, and secularization. As a part of this surge towards "progress", women discarded henna as outdated, superstitious, and an unwelcome symbol of a repressive past. As Turkish women adapted western dress, makeup, and tastes along with literacy, the vote, and legal rights, henna was left to the rural women. This departure from the past paralleled social revolutions in Russia, China, and other countries across the world. The effects of these reforms were positive in many ways, especially in the area of women's rights, but in henna-using countries, henna was often discarded as a symbol of "the bad old times". By mid-20th century Turkey and other countries, henna was perceived as quaint, at best. At worst, hennaed hands were an embarrassment. With no demand for henna, the old skills were forgotten and the few old women who still remembered henna, marked occasions with a few orange dabs, from a dusty, stale, long unsold box of henna in the market. Brides who aspired to be "modern" purchased western cosmetics, white wedding gowns, and danced to pop music ... though at the beginning of the 21st century has appeared again in tourist areas as a novelty. References:

Akurgal, E. The Art and Architecture of Turkey Rizzoli, 1980 Atil, E. The Age of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York Barber, N. "The Sultans" Simon and Schuster, New York, 1973 "Codex Vindobonensis" 1590 Croutier, Alev Lytle “Harem: The World Behind the Veil” Abbeville Press 1989 da Zara, Bassano “I Costumi et I modi particolari de las vita de Turchi” 1545 Penzer, N. M. "The Harem" Bookplan, 1936 Wheatcroft, A. The Ottomans Viking, 1993 References: Akurgal, E. The Art and Architecture of Turkey Rizzoli, 1980 Atil, E. The Age of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York Barber, N. "The Sultans" Simon and Schuster, New York, 1973 "Codex Vindobonensis" 1590 Croutier, Alev Lytle “Harem: The World Behind the Veil” Abbeville Press 1989 da Zara, Bassano “I Costumi et I modi particolari de las vita de Turchi” 1545 Penzer, N. M. "The Harem" Bookplan, 1936 Wheatcroft, A. The Ottomans Viking, 1993

Alex Morgan's Tulips of Topkapi and Jessica McQueen's Arabesque have beautiful henna patterns adapted from Ottoman art! Available through TapDancing Lizard Back to the index of Turkish Henna The Henna Page Main Index http://www.hennapage.com/henna/mainindex.html *"Henna,

the

Joyous Body Art"

the Encyclopedia of Henna Catherine Cartwright-Jones c 2000 registered with the US Library of Congress TXu 952-968 |